|

Strategy for Malaria Elimination in the Greater Mekong Subregion (2015-2030) (Part 2)

Key interventions and supporting elements Key interventions are aimed at guiding regional- and country-level actions to eliminate malaria in the GMS context, with the proposed elimination strategy based on the following three key interventions and two support elements. The three key interventions are: The three key interventions are: 1. Case detection and management 2. Disease prevention in transmission areas 3. Malaria case and entomological surveillance. The two supporting elements are: 1. Expanding research for innovation and improved delivery of services 2. Strengthening the enabling environment.

Key interventions Key intervention 1. Case detection and management Components of case management Universal coverage with early diagnosis and effective treatment reduces morbidity, mortality and transmission. Case detection can be done through passive case detection (PCD), active case detection (ACD), as well as screening for malaria cases in high-risk groups. In the elimination phase, case detection and management activities aim to find and treat all cases according to national treatment policies and ensure that every case and treatment outcomes are reported to the national surveillance system. Case management and surveillance are intimately linked. In the transmission-reduction phase, case management is primarily oriented towards decreasing morbidity and mortality. In the elimination phase, case management becomes part of surveillance, which has the goal of preventing secondary transmission from any case. Table 1 lists the main differences between case management policies and practices in the transmission-reduction and elimination phases. Table 1. Case management in transmission-reduction and elimination phases | Transmission-reduction phase | Elimination phase | Purpose | Early diagnosis of symptomatic cases and effective treatment of all detected cases to reduce transmission, morbidity and mortality. | Early detection and treatment of all cases to prevent onward transmission. | Diagnosis policy | All suspected cases should be examined by RDT or microscopy. | All suspected cases must be examined by RDT or microscopy. | Treatment policy | P. falciparum: ACT as defined by national policy; single dose of PQ is recommended. P. vivax: CQ, provided that efficacy is confirmed by TES, otherwise ACT. | P. falciparum: ACT as in transmission-reduction phase; single dose PQ is mandatory. P. vivax: CQ or ACT as in the transmission reduction phase; PQ is mandatory;G6PD status should be used to guide administration of primaquine for preventing relapse. When G6PD status is unknown and testing not available, decision must be based on assessment of risks and benefits of adding primaquine. | Cung c?p d?ch v? | All public health services. Private medical practitioners. Not-for-profit sectors (NGOs). Informal private sector. Community-based services. | Same as transmission-reduction phase, but over-the-counter sale of antimalarial agents prohibited and informalprivate sector not allowed to treat malaria cases; service provision by other sectors (e.g. military, corporate sector) follows national norms and is monitored. Largely, universal coverage has been achieved. | Standby treatment | May be considered for certain migrant groups if it is impossible to provide diagnosis. | The same as in transmission-reduction phase, but this should be exceptional and be monitored. |

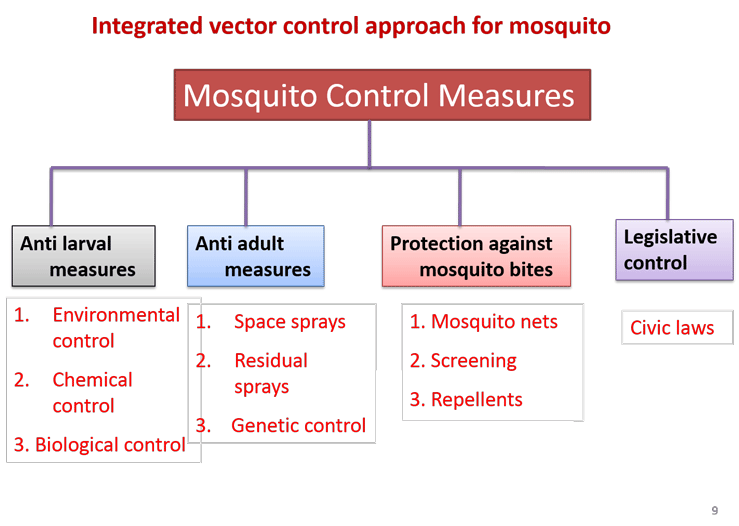

Case detection The detection of malaria infection is primarily based on blood examination by RDTs or microscopy. With QA in place, both are now suitable for surveillance and case management, but microscopy has advantages for follow-up of patients, detection of gametocytes and determination of parasite density. Rapid diagnostic tests (RDTs) for detection of P. falciparum and/or non-P. falciparum infections should be available at health facilities and community-level services, while quality-assured microscopy should be made available at hospitals and malaria laboratories at district and higher intermediate and central levels. Determining what kind of diagnostic methods or their combinations to use at various levels requires analysis by each national programme. Diagnostic methods with a higher sensitivity than RDTs and microscopy, such as polymerase chain reaction (PCR) or other molecular-based techniques, can detect parasite carriers with very low parasite densities. However, the definitive roles of these more sensitive methods in the transmission-reduction and elimination phase will depend on the epidemiological significance of low-density infections and the future availability of user-friendly, rapid, affordable tools. Currently, most molecular-based methods require a laboratory with sophisticated equipment and skilled personnel, and therefore samples must be transported for analysis. This approach may be appropriate in large scale surveys settings but not for case management. Treatment Treatment for P. falciparum and non-P. falciparum malaria should be based on national treatment policies and WHO guidelines. Currently, all medicines recommended for the treatment of uncomplicated P. falciparum malaria are ACTs. Treatment should include primaquine to eliminate gametocytes, responsible for mosquito-borne transmission of malaria. Primaquine may cause haemolysis in G6PD deficient patients but for treatment of P. falciparum malaria, a safe low dose of primaquine has been identified and recommended by WHO. In patients infected with P. vivax, the standard treatment is CQ or ACT plus a 14 day course of primaquine. The G6PD status of patients should be used to guide administration of primaquine for preventing relapse. For P. vivax malaria, the safest solution is screening for G6PD deficiency prior to primaquine administration. Recently, more user-friendly, point-of-care G6PD tests have become available. These tests, however, cannot identify all patients at risk of haemolysis (e.g. female heterozygotes), and experience with their use in the field in the hands of routine health workers is limited. Therefore, operational research and/or piloting with monitoring are needed. Universal coverage of case management Achieving universal coverage with case management requires three channels of service delivery to be considered: public, private and community based. The optimal mix of these will vary among and within countries. While malaria incidence remains high, maximizing coverage through all three channels is likely to be the best approach, provided efforts are made to improve quality. In the elimination phase, the roles for each channel should be defined, depending on countries' situations and local conditions, to ensure optimal case management, surveillance and reporting in all areas. The public health sector In areas well served by health facilities, all health institutions in the sector serve as free diagnosis and treatment centres for malaria. Restricting certain services to public health facilities can help to ensure that they are delivered according to standard guidelines. However, the public health sector in some countries remains under-resourced and challenged by human resources and supply chain issues, while the health service network coverage is inadequate, especially in thinly populated areas. The private health sector Several national programmes have engaged with the private sector for delivery of malaria curative services. The private health sector includes medical practitioners, licensed pharmacies, non-licensed drug vendors, authorized services belonging to private companies catering to their employees, and not-for-profit services such as nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) and faith-based organizations. All of these can be involved in case management, provided that the public sector invests in communication, training, monitoring and, in many cases, provision of diagnostics and medicines. NGOs can have a key role in providing quality services. The informal private sector (in the form of drug vendors) is a major source of irrational treatment and substandard medicines. The strategies for addressing this issue can range from prohibiting them from treating malaria to fully enlisting them. Such schemes usually include an element of social marketing. Each country needs to develop a strategy for determining the most appropriate role for various types of private providers. In the elimination phase informal providers refer cases only and are not involved in treatment. Community-level services Most GMS countries already have well established free community-based case management services for malaria. Technically, community service providers are a part of public services, but the providers themselves are usually volunteers, who depend on the support of their community or an NGO, or are paid by performance. These services are usually the best solution for remote areas. Services for mobile and migrant populations Providing services for mobile and migrant populations is essential. Elimination will not be achieved unless these population groups have access to malaria protection measures, early diagnosis and treatment. Mobile populations are difficult to reach for a number of reasons, including undocumented status for some. Improving their access to health services can be a complex multisector task (4). Although some migrants employed in informal or even illegal labour may prefer to avoid any contact with public services, others in regular legal employment may be easy to work with if they and their employers are approached in a sensitive manner. Different modalities for service provision can be considered. Thailand's 'one-stop centres' for migrants provide information on malaria and may distribute LLINs. In Cambodia and elsewhere, mobile malaria workers recruited from migrant groups by the malaria programme appear to have been successful in delivering curative services. For solitary migrants and smaller migrant groups, it may be more effective to set up fixed-schedule mobile clinics to give treatment at specific times or places. Screening of migrants, including at border crossings, has worked well in some places. For the management of such differentiated services, intersectoral cooperation and proactive and systematic collection of information on migrants are key. Province-level malaria units should include mobile teams for managing malaria in mobile and migrant populations. These teams may overlap with elimination-phase surveillance teams and should travel to wherever migrants spend time, including key transit points, and ideally be authorized to work across borders when necessary. Mobile teams should also work with migrant recruitment agencies and with health authorities in places where migrants start their journeys (5). Quality assurance Quality assurance of diagnostics, treatment, patient care and surveillance is important in both transmission-reduction and elimination phases. The only difference is that QA of microscopy is even more essential in the elimination phase. Diagnostics It has become easier for countries to procure quality RDTs (6), however, there is still a need for better methods to ensure product quality control at point of care prior to use. In the elimination phase microscopy QA requires considerable investment and attention (7). Antimalarial medicines For case management, it is critical that medicines are of good quality. Efforts to eliminate counterfeit and substandard medicines carried out over many years in GMS countries must be continued and enhanced. Areas of work fall into the following broad categories: - strengthening drug regulatory agency functions to: + eliminate artemisinin monotherapy products and register only quality-assured medicines, and diagnostics; + strengthen quality assurance during and after registration to prevent the manufacture and sale of substandard products; + intensify surveillance to detect and eliminate the sale of spurious, falsified, falsely labelled and counterfeit products; + improve national capacity for quality-control testing and cross-border enforcement activities to reduce the flow of counterfeit and substandard products; - improving supply management to reduce any shortages and prevent stock out in the public supply chain; - engaging the private sector to improve the availability of quality-assured products and eliminate substandard, falsified and counterfeit drug sales; and - improving rational and responsible use of all malaria medicines to reduce unnecessary overuse that may contribute to resistance. Key areas of focus include ensuring a sustained global supply of diagnostics and medicines; promoting the development of innovative technologies to address market shortcomings; and ensuring the quality of available malaria commodities through adequate registration, good procurement practices and regular quality monitoring. Achieving this will require strong regional and national coordination of interventions related to pharmaceutical and commodity supply (including streamlining of stakeholders' efforts in this area), as well as cross-border and regional coordination. QA of case management services Supervision is the key to QA of patient care, and should be applied with clear protocols and monitoring systems. The directly observed treatment (DOT) principle should support patient adherence and monitoring. The problem is that many patients cannot remain in one place for the duration of the treatment. Until more evidence is available, programmes must conduct their own evaluation on where and when to apply DOT. Standby treatment Standby treatment - decided without a diagnostic test by the patient or somebody close to the patient - is a common practice, which has often been incriminated in relation to resistance to antimalarials in the GMS. With greatly improved service coverage and especially the availability of RDTs, this should now be much less needed. However, some mobile groups may be so small and isolated that standby treatment may be an option. Key Intervention 2. Disease prevention in transmission areas Vector control measures for transmission prevention The selection of appropriate vector control interventions is to be guided by eco-epidemiological stratification informed by malaria case and entomological surveillance data. Implementation should be within the framework of integrated vector management. Use of insecticidal interventions will be guided by technical recommendations provided in the Global plan for insecticide resistance management in malaria vectors (42). Table 2 lists the main differences between vector control in the transmission-reduction and elimination phases. Table 2. Vector control in transmission-reduction and elimination phases

| Transmission-reduction phase | Elimination phase | Purpose | To reduce transmission intensity. | To reduce onward transmission from existing cases. | Stratification of malaria situation | Definition of major eco-epidemiological strata, with allocation of appropriate vector control by strata. | Foci-based stratification, with categorization of active and potential foci. | Vector control policy | Universal coverage of all at-risk populations with LLINs or IRS and supplementary measures where appropriate (e.g. long-lasting insecticidal hammock nets, larval source management, repellents) with special emphasis on mobile and migrant populations. | Geographical reconnaissance. Full coverage (100%) of all populations in active foci of malaria, with a view to interrupting transmission in a focus as soon as possible. Maintain universal coverage of at-risk populations with vector control in all areas in which malaria transmission has been interrupted. | Entomological surveillance | Yes | Yes | Monitoring and management of insecticide resistance | Yes | Yes | Epidemic preparedness and response | Yes | Yes | Research, technology, monitoring and evaluation | To introduce a GIS-based database on malaria vector bionomics and insecticide resistance. To consider operational research on technical and operational feasibility, effectiveness and sustainability of current or new vector control approaches. | A central repository of information related to entomological monitoring, and application of chosen vector control interventions established and fully functional. |

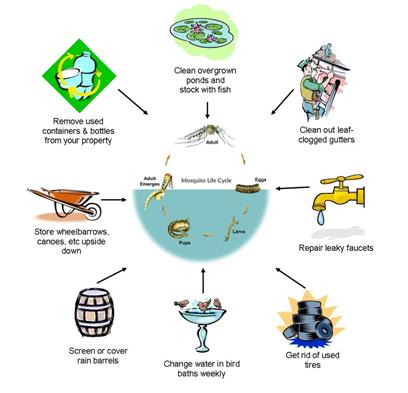

GIS, geographic information systems; IRS, indoor residual spraying; LLIHN, long-lasting insecticidal hammock net; LLIN, long-lasting insecticidal mosquito net. Long-lasting insecticidal nets (LLINs) LLINs have been shown to reduce malaria incidence by around 30% in forested areas in the GMS, despite the local malaria vectors being somewhat exophilic (outdoor resting) and exophagic (outdoor biting) (8, 9). LLINs are a core malaria prevention measure, widely used to reduce transmission and provide personal protection. To achieve and maintain universal coverage of populations in areas of transmission requires distribution of LLINs based on actual needs. Analysis of the age and gender of malaria cases at village level, backed by an analysis of treatment-seeking behaviour in the different population groups, should indicate whether transmission is occurring locally, and thereby allow more strategic and cost-effective targeting of LLINs and related interventions. Distribution of LLINs will be done through mass campaigns, coupled with locally appropriate and gender sensitive IEC/BCC to ensure high and correct usage. Factors to be considered when nets are distributed include which members of a household share a sleeping space. A population-wide coverage level of one net per two persons at risk does not necessarily mean that each household will have enough nets to protect all household members. Maintenance of coverage can also be an issue, with the effective lifetime of nets known to vary between settings. To maintain high levels of coverage and usage between mass campaigns, there should be a distribution system to continuously make additional or replacement nets available. Appropriate continuous distribution systems should be identified for each specific setting. Points of contact such as shops, plantation owners, the military and community malaria workers may be involved. While use of antenatal clinics may be feasible in forest villages, in forest-fringe environments this may not be suitable as risk is usually concentrated in adult males. Managers at all levels need real-time information on operations, to address gaps and problems before they have a negative impact. Currently, data on coverage of LLINs is often collected by surveys carried out at intervals of one year or more and may have limited geographical scope. There is a need for more dynamic monitoring of LLIN coverage to allow programmes to react in a timely manner to low coverage levels caused by losses or the arrival of mobile population groups in a particular risk area. Indoor residual spraying The effectiveness of indoor residual spraying (IRS) is constrained by factors similar to insecticide-treated mosquito nets (ITNs) and by the open nature of the construction of typical shelters in forested areas of South-East Asia. Spraying is carried out in Viet Nam in areas with low net coverage, and in other countries as an outbreak response intervention. In Cambodia, IRS has been a part of the strategy for eliminating artemisinin resistance. The consensus among experts is that regular preventive IRS is not an appropriate option in the GMS except in special circumstances, such as in areas where ITNs are not accepted for cultural reasons or for use as a resistance management strategy. Focal IRS should, however, be part of the set of tools that can be applied in outbreaks or as a short-term measure, to help interrupt transmission in persistent transmission hot spots where surveillance data indicate local transmission. IRS operations across the GMS are conducted in different ways and are in need of better QA. Possibly because of the limited scale of operations, procurement cycles sometimes encounter serious delays, and there is a need to address stockpiling and related issues. These operational issues should be rectified by informed needs estimates and good planning. Larval source management Larval source management (LSM) refers to all measures to reduce mosquito breeding, including targeting aquatic habitats with larvicides and environmental modification or manipulation. LSM is applicable where breeding sites are few, fixed and findable. Currently, there are 12 WHO recommended mosquito larvicides representing five different mode of actions although most current formulations have limited residual efficacy, and the role of LSM in insecticide resistance management is as yet undetermined.

Identification of all breeding sites is notoriously difficult in malaria-endemic forest and foothill areas of the GMS, and although larvivorous fish are used in some programmes, the confidence in their effectiveness is low. However, new methods of application of insect growth regulators make it possible to consider their use in situations where the contact between humans and vector populations is limited to defined areas.

Long-lasting insecticidal hammock nets Long-lasting insecticidal hammock nets (LLIHNs) can provide some protection for forest workers and other high-risk mobile and migrant groups, but have only been adopted on a large scale in Cambodia. While LLIHN have not yet been assessed by WHO, their use has potential in some settings (12, 13). These may be most appropriate in areas where there is already a culture of hammock net use (e.g. Viet Nam), though experience from Cambodia suggests that this situation could be changed through communication and delivery. Where LLIHNs are not already part of national strategies, evidence on acceptability and effectiveness may be generated through local pilot studies. Work will be required to identify the best delivery mechanisms for each of the various target groups. In Cambodia, the malaria programme is making LLIHNs available as part of 'forest packs', containing a hammock, an LLIHN, personal repellent and information on malaria prevention and treatment, which are delivered through strategically positioned private outlets.

Spatial repellentsSpatial repellents may have potential as a supplementary measure to LLINs and IRS for reducing human-vector contact and controlling malaria transmission and disease. However, despite increased research efforts during the past several decades, the mechanism of repellency is not yet fully understood. The utility of spatial repellents for both malaria and dengue control is currently under evaluation in multi-country trials (39), and outcomes will inform the integration of this tool into vector control strategies in the GMS.

Personal protective measures Vector control products that protect specific populations in certain circumstances but do not necessarily contribute to community protection also have public health value and importance (40). These include hammocks, clothing, curtains, wall hangings, material-based emanators, blankets and tents. However, the safety, acceptability and effectiveness of specific products within these paradigms have yet to be comprehensively evaluated by WHO and hence their contribution to malaria control and the conditions governing their appropriate deployment have not yet been defined. The burden is therefore on national programmes to generate sufficient local evidence to inform their use.

Personal repellents and insecticide-treated clothing may be of interest for application in forest-related malaria settings, where transmission takes place outdoors while certain risk groups are active. Personal repellents must be applied repeatedly; thus, there needs to be high compliance and a regular supply from the programme or an employer and availability for individuals to purchase. So far, these delivery channels have not been established. Insecticide-impregnated clothing has the advantage of requiring limited behaviour change. Recent intervention trials using permethrin-impregnated clothing have shown a marked reduction in the risk of malaria infection among users, but there is still a lack of data on skin absorption and potential adverse effects. The use of pyrethroid-treated clothing would not be appropriate in areas where there is pyrethroid resistance. Drug based interventions Chemoprophylaxis Chemoprophylaxis should be provided to international travellers going to high-risk areas in and outside the GMS, and is particularly important in the elimination phase. The drugs for chemoprophylaxis are currently limited to mefloquine, doxycycline and atavoquone-proguanil (14). Mass drug administration The emerging threat of antimalarial drug resistance and the renewed focus on malaria elimination has been accompanied by reconsideration of mass drug administration (MDA) as a means for rapidly eliminating malaria in a specific region or area. In MDA, the objective is to provide therapeutic concentrations of antimalarial drugs to as large a proportion of the population as possible in an area in order to cure any asymptomatic infections and also to prevent reinfection during the period of post-treatment prophylaxis. During mass campaigns, every individual in a defined population or geographical area is requested to take antimalarial treatment at approximately the same time and at repeated intervals in a coordinated manner. This requires extensive community engagement to achieve a high level of community acceptance and participation. The optimum timing depends of the elimination kinetics of the antimalarial. Depending on the contraindications for the medicines used, pregnant women, young infants and other population groups may be excluded from the campaign. Thus, the drugs used, the number of treatment rounds, the optimum intervals and the support structures necessary are all context-specific and are still subject to active research. MDA rapidly reduces the prevalence and incidence of malaria in the short term, but more studies are required to assess its longer-term impact, the barriers to community uptake, and its potential contribution to the development of drug resistance. The role of MDA in acceleration towards elimination is currently being evaluated by WHO.

Key intervention 3. Malaria case and entomological surveillance Malaria case surveillance The elimination phase is defined by the application of malaria case surveillance according to specific and rigorous standards. Table 3 presents the main differences between malaria case surveillance in the transmission-reduction and elimination phases in the GMS. The transition from transmission-reduction to elimination phase will require revision of guidelines, recruitment of staff, training and supervision (3). Malaria case surveillance in the elimination phase aims at: - detecting and notifying all malaria infections, and ensuring that they are given early treatment, to prevent secondary cases; and - investigating each malaria case to determine whether it was locally acquired or imported; case investigation and classification should be completed within one to three days. Once a local case of malaria has been detected and notified, a focus investigation is carried out by malaria staff to assess the risk of transmission in the locality where malaria occurred. Design of malaria case surveillance The design of a malaria surveillance system depends on the level of malaria transmission and the resources available to conduct surveillance. In the transmission-reduction phase, there are still many cases of malaria; hence, it is not possible to examine and react to each confirmed case individually. Instead, any response is based on aggregate numbers, and action is taken at a population level. As transmission is progressively reduced, it becomes increasingly possible (and necessary) to track, investigate and respond to individual cases. The government can regulate reporting by formal health providers which makes it easier to incorporate details into national malaria surveillance systems. In contrast, the informal health sector is more difficult to include, because of a lack of regulation and enforcement. In the elimination phase, the roles for each provider should be clearly defined, depending on each country's situation and local conditions. This will help to ensure that quality malaria data are provided on a timely basis from public, private and community-based health sectors, and from autonomous health services, such as military, border forces, police, private companies and development projects. Table 3. Surveillance policies and practices in transmission-reduction and elimination phases | Transmission-reduction phase | Elimination phase | Purpose | To allow targeting of interventions, detection of potential outbreaks and tracking of progress. | To discover any evidence of the continuation or resumption of transmission; detect local and imported cases as early as possible; investigate and classify each case and focus of malaria; provide a rapid and adequate response; and monitor progress towards malaria elimination. | Data reporting, recording and indicators used | Private sector is requested to report cases. Aggregate numbers of outpatients, including those with uncomplicated P. falciparum malaria. Number of inpatients with severe or complicated malaria, and deaths due to malaria. Conventional malariometric indicators (API, SPR, ABER). | Malaria is a notifiable disease. Private sector must report every case by law. Number of local and imported cases, and residual or new active and potential foci of malaria. | Detection method | PCD at all levels of health system. ACD in high-risk groups, especially migrants. | PCD at all levels of health system. ACD to fill gaps in PCD system, in order to detect infections as early as possible, with particular focus on high-risk groups. Reactive ACD in case investigation and clearing of foci. | Case and foci identification, investigation and classification | No | Yes | Technology, monitoring and evaluation | Consolidate the use of new tools such as web-based data transmission, volunteer reporting via SMS. Introduce case-based malaria surveillance. | Adequate case- and foci-based malaria surveillance fully functional across the entire territory of a country. National computerized malaria elimination database or register established. National malaria elimination monitoring committee set up. | Data elements | Aggregate counts, health facilities or districts/villages. | Case based, foci. | Case definition | Confirmed clinical cases. | Any malaria infection (symptomatic and asymptomatic). | Case investigation | Admissions, deaths. | All cases. | Timescale | Monthly. | Immediate notification. |

Monitoring of resistance to antimalarial agents Monitoring of resistance should be done in each country, based on most recent WHO guidelines. First-line treatment efficacy should be monitored through therapeutic efficacy studies (TES), where blood samples are also collected and analysed for molecular markers of resistance. Once the number of patients falls to low levels, it is no longer possible to perform TES; instead, the focus should be on attempting to follow up all patients(especially P. falciparum patients) on the days specified in the WHO TES protocol. Human resources and infrastructure for surveillance in the elimination phase Health staff and malaria volunteers can usually be trained to investigate malaria cases. In hospitals, this is often done by laboratory technicians. The investigation form, when filled in, is normally forwarded to a province or district malaria officer, who reviews it, classifies the case and communicates it to higher levels, where it is again reviewed. The investigation and management of foci requires a team that includes staff trained in epidemiology, entomology and operations management. Such mobile teams normally need to be present at province level. Timeliness of response is key, and China provides a good example with its '1-3-7 initiative'. This requires malaria cases to be reported within one day, full case investigation to be conducted within three days, and response actions to be taken within seven days. Such a scheme makes it clear to health workers what is required; it also allows the monitoring of performance against a benchmark (15). Detection and prevention of malaria outbreaks and epidemics It is essential to ensure that mechanisms are in place to predict outbreaks where possible, detect them at early onset and rapidly respond with a comprehensive package of services to halt transmission at the earliest opportunity. ACD, focused screening and treatment (FSAT) and focal-responsive IRS, combined with early detection and prompt treatment of malaria through the existing health services, have proven to be effective in containing transmission and preventing the further spread of epidemics in affected areas. In accordance with the most likely risk scenarios, national contingency plans should be worked out with an indication of the channels to be used to import any necessary supplies and an identification of resources to be rapidly mobilized. The effectiveness of preventive action is heavily dependent on the speed with which national health services mobilize the necessary resources. Entomological surveillance Knowledge of entomological aspects is key to selecting appropriate vector control interventions and monitoring their impact on mosquito populations. Entomological surveillance can include assessments of species distribution, densities, aquatic habitats, feeding and resting behaviours. Monitoring of the susceptibility of vector populations to insecticides used or planned for use is critical. Resistance to DDT has been reported for malaria vectors from all five countries in the GMS, and pyrethroid resistance has been reported for Cambodia, Thailand and Viet Nam. Increased use of pyrethroids in agriculture is likely to exert further selective pressure for resistance and may well prove to be an important risk factor (10). Entomological surveillance systems should be established to actively monitor for changes in key parameters such as species composition and sensitivity to insecticides in relation to interventions and malaria epidemiology. Resultant entomological data can be used to inform programmatic decisions such as the choice of insecticide for IRS or priority areas for combining LLINs and IRS for resistance management purposes. Spot checks may be conducted randomly in selected areas to supplement routine entomological observation or to obtain a clearer indication of the effects of control measures. Entomological foci investigations are undertaken in areas of new or persistent active foci to determine why there is transmission (e.g., to ascertain whether it is due to insecticide resistance or to a shift to outdoor biting vectors) and to identify the best approaches for maintaining effective control or sustaining elimination. Entomological intelligence is also useful to evaluate risk of reintroduction where malaria-free status has been achieved recently. Establishing and maintaining such surveillance systems requires human and infrastructural capacity - vector technicians and facilities such as insectaries and laboratories appropriately placed to support vector sampling, identification and characterization at sites selected based on eco-epidemiological representativeness. Countries need to ensure that they maintain a core group of trained entomologists to carry out monitoring, make recommendations about any necessary changes in interventions or delivery strategies (11), and to address any elimination-specific challenges. Decisions on the monitoring and management of insecticide resistance should be informed by national plans developed on the basis of a comprehensive situation analysis. Supporting elements The strategy has two supporting elements, each covering a number of key requirements for the successful implementation of the GMS elimination strategy. 1. Expanding research for innovation and improved delivery of services - Development of novel tools and approaches to respond to existing and new challenges, such as outdoor biting and varying patterns of population mobility. - Operational research to optimize impact and cost-effectiveness of existing and new tools, interventions and strategies. - Action to facilitate rapid uptake of new tools, interventions and strategies. 2. Strengthening the enabling environment - Strong political commitment and adequate financial support for malaria elimination. - Capacity development appropriate to the implementing strategy. - Health systems strengthening to facilitate malaria elimination. - Policies for delivery of services to meet the needs of mobile and migrant populations. - Intersectoral collaboration and community involvement. - Advocacy to support collective action. - GMS regional functions (including coordination, technical support, capacity-building, cross-border or regional collaboration, monitoring of progress, priority research and information sharing). The rest of this section discusses each of these key requirements for the successful implementation of the GMS elimination strategy. Supporting element 1. Expanding research for innovation and improved delivery of services The potential novel interventions described here will require a concerted research effort to move quickly towards operational adoption. Equally important is operational research that addresses bottlenecks in operations and finding innovative ways to effectively deliver services to hard-to-reach populations. Among the potential areas of research for innovation and improved delivery of services are: - mass drug administration; - triple combination therapies; - improved molecular diagnostic techniques; - test kits for G6PD for community level; - endectocides reducing the survival or fecundity (or both) of mosquitoes that feed on - those people, thus reducing vectorial capacity; - vector control, including more cost-effective deployment of LLINs, alternative - interventions for personal protection, and spatial repellents; and - vaccines. It is important to distinguish between novel interventions that would require limited operational research to become applicable (e.g. kits for detection of G6PD status, repellents and insecticide-treated clothing, and molecular diagnostic techniques) and those that still require a systematic, multidisciplinary and objective-oriented research effort, such as endectocides and vaccines.

The main lesson from the current status of implementation of standard methods is that any tool to be introduced should be accompanied by operational or implementation research to optimize coverage and quality, and limit wastage. Between policy adoption and wide application of a novel intervention, there is usually an interval of at least three years. To meet timelines, especially for P. falciparum elimination, it will be necessary to introduce and scale up novel interventions rapidly in eligible areas, once the interventions are approved. New interventions used should be effective for areas and population groups where standard interventions have already had a major impact, but are not achieving the annual parasite incidence 1/1000 benchmark or, having achieved the benchmark, are not reaching zero. Supporting element 2. Strengthening the enabling environment Strong political commitment and adequate financial support for elimination To succeed, the GMS malaria elimination strategy has to be backed by effective national policies, in which: - a high-level multisectoral national malaria elimination committee or task force is set up and functional; - political commitment is translated into adequate and sustained financing of malaria elimination; - the health system is strengthened and is able to deliver basic health services, including interventions for malaria elimination; - malaria is made a notifiable disease; - adequate case-based malaria surveillance is established and fully functional across the country; - the planning of elimination measures is based on epidemiological investigation and classification of each malaria case and focus; - universal coverage of disease management is supported; - full coverage with proven vector-control measures of all populations in active foci of malaria; and - a national malaria elimination database is set up and operational. Successful malaria elimination requires adequate planning and budgeting (permitting programme staff to focus on implementation issues rather than fund-raising), and activities should be conducted with sufficient lead time and the necessary mobilization of resources. A strong participatory approach (with clear roles and responsibilities of all partners concerned), and regular exchange of information and consultations between WHO, partners and national programmes, should be encouraged and promoted, to enable the regional partnership to function more effectively and to better coordinate malaria elimination efforts and facilitate resource mobilization. It is crucial for every GMS country to ensure that adequate financial resources are available during all phases of the strategy. Countries must be prepared to increase national investments. As an elimination programme proceeds, the costs shift towards human resources, and, when the country is malaria free, towards general health services. Greater flexibility is also needed as the epidemiology changes. With such changes, government funding is likely to be more efficient. Therefore, national commitment, which is so crucial for the achievement and maintenance of elimination, will be gauged by the extent to which domestic investments are increased, and this becomes important in leveraging donor support. Nonetheless, external funders should remain mobilized to support the common long-term objective. Elimination of malaria in the GMS is both a regional and global public good, because addressing resistance of P. falciparum to antimalarial agents is both a driver and an outcome of the GMS elimination programme with global repercussions. Thus, it merits continued support from global as well as emerging regional development partners. Stability of funding is essential for an elimination programme as delays in disbursements can lead to malaria resurgence, where gains made over five years can be lost in less than five months. Various options for innovative financing to support malaria elimination programmes have been reviewed (16), and a combination of some of these mechanisms might well support malaria elimination. The Asia Pacific Leaders Malaria Alliance (APLMA) is well placed to analyse which schemes would be best adapted to country-specific situations, or collectively to the GMS malaria context. However, this requires strong involvement of all the national governments concerned and relevant partners. Capacity development appropriate to the implementing strategy Technical capacity within national programmes has declined in several GMS countries in recent years due to a number of factors, including an ageing workforce, limited opportunities for high-level training, and increased staff attrition due to recruitment by partner agencies. Urgent steps will need to be taken in affected countries to strengthen capacity at all levels of the health system in line with the demanding requirements for elimination. Health systems strengthening to facilitate malaria elimination The health systems in most of the GMS countries need to be strengthened in terms of human resources, services, financing, information systems and governance. Conversely, all the GMS countries have strong economic growth and their health systems are improving. The following health system functions are of particular concern, and in decision-making and planning for elimination they should be analysed at the highest level of the ministry of health and possibly at cabinet level. - Human resources Due to the need for strong surveillance systems and high quality of all operations, human resources must increase at all levels. In the malaria elimination phase, some personnel should be devoted to malaria; alternatively, general public health staff may have sufficient time for malaria surveillance and response, in which case they should be trained accordingly. Staff must be motivated and maintained until transmission is interrupted, and possibly thereafter, at least for some time. Human resources required will appear to be disproportionate to the disease burden, and this can be justified by referring to overall programme goals. - Financial allocations During the elimination phase financial allocations need to be maintained, despite low burden and even after the attainment of malaria-free status, because surveillance systems to prevent reintroduction are costly in countries with high receptivity and vulnerability (17). Donors will expect to pay decreasing proportions of the elimination budget, because the major expenditures are for human resources. Thus, after interruption of transmission, it is unrealistic to expect significant donor support. - Governance and regulation The two main issues are pharmaceutical regulation and regulation of the private sector. In the elimination phase, malaria must be a notifiable disease. Enforcing the relevant legislation will be a major challenge in countries where most fever patients seek care in the informal private sector. There is no example of a country having eliminated malaria in this situation. - Administrative capacity The recruitment and maintenance of human resources (from the village volunteer to the programme manager) and access to services depends not only on commitment and financial allocations, but also on the capacity of the system to plan and implement budgets, execute payments on schedule, and rapidly reallocate or mobilize funds to deal with unexpected events. Administrative disruptions can lead to malaria epidemics and derail elimination programmes. - Leadership and management in the malaria programme Adoption of a malaria elimination strategy increases the need for leadership and management in malaria programmes. Operations will need to be managed with rigour and flexibility, supported by robust monitoring and quality control. Programmes will need to be responsive to the evolving needs of the elimination effort and risks will need to be taken in the interests of innovation and to accelerate programmatic impact. The reality is that some malaria programmes in the GMS have lost staff in recent years, because of competing priorities. Elimination activities are not necessarily cost-effective in the short run and do not always respond to the population's perceived needs or necessarily support the development of health systems. It is not surprising that in many of the elimination success stories around the world the presence of a respected and inspiring leader was a crucial element. NGOs are often well placed to provide support which extends to distribution of LLINs, surveys, insecticide resistance studies and health education. In summary, for a programme having elimination as its objective the following capabilities must be present at the central level, and to some extent, at other levels: - technical competence; - ability to advocate, communicate and convince; - ability to manage human and financial resources and time; - ability to work with partners and other sectors, and within the health sector; - ability to train other professionals; - ability to interpret and use epidemiological and operational information; and - information management skills. In addition, when adopting a malaria elimination objective, higher levels of ministries of health must ensure: - malaria elimination is recognized at cabinet level as a national concern, led by the ministry of health and involving all relevant sectors; - there is oversight by a higher level than the ministry of health (or at least by the top level of the ministry of health); - reports are scrutinized by the cabinet or a parliamentary committee; and - the malaria programme is given administrative power to re-programme and react rapidly to emergencies, recruit additional short-term staff as needed and mobilize funds. Policies for delivery of services to meet the needs of mobileand migrant populations At-risk populations will need prompt access to free quality services, despite low population density, mobility, different languages and undocumented status. This requires sustained investments on the part of the ministry of health, including for general health service staff in remote areas. Intersectoral collaboration and community involvement Social and environmental determinants of malaria are not the sole responsibility of a single sector (18).For example, although the association between rubber plantations and malaria is well known in South-East Asia, the potential for re-emergence of malaria should receive substantially more attention from economic, agricultural and environmental planning bodies. Understanding the influence of land use change on malaria occurrence is critical for shaping future surveillance strategies (19). As highlighted by the recent work on developing a multisectoral approach to malaria (18), several recommended strategies could be seen as applicable to GMS countries for greater coordination between health and non-health sectors, as well as within the health sector. - Trade and industry sectors should be involved in developing corporate social responsibility programmes for improved health which includes malaria prevention and treatment. Large-scale infrastructure, agriculture, mining, oil and gas exploration projects are attracting significant local and foreign investment and labour forces in GMS countries. There is a need for clearer guidance on the type of services companies could provide (e.g. awareness, vector control, case management and surveillance), which could be achieved through a menu of options relating to the nature of business(20). - Evidence to demonstrate the clear economic advantage of malaria investment (building a business case) needs to be presented (18). Opportunities for integrating malaria in financing mechanisms for other non-health sectors that impact malaria, such as food security and adaptation to climate change, should be sought. In doing this, it is important to realize that there is no one-size-fits-all solution for private sector engagement in country elimination plans, and that the right actions must be identified per sector and per company, based on comparative advantage and strengths. As shown by recent initiatives in Myanmar, one method that can be initiated by national malaria programmes is conducting a thorough mapping exercise of companies (for a start among those that have corporate social responsibility programmes or those that have already malaria prevention and control activities) and their geographic/population catchment areas. - A few countries in the GMS have documented Public Private Partnership/Public Private Mix(PPP/PPM) initiatives for diagnosis and treatment as well as prevention. In this regard, two recommendations can be proposed: (a) country malaria elimination programmes develop a PPP/PPM legislative framework to clarify how the private sector should work with government/public sector entities and work in consultation with stakeholders and in-country partners, as initiated in Myanmar through its accreditation scheme with companies and other non-state actors; and (b) national programmes should include in their elimination plans participatory research or other methods to determine the incentives for other sectors to contribute to malaria control. These may vary for different sectors: agriculture, climate change and food security, the impact of urbanization and population mobility on malaria; and the potential of the military in implementing malaria control (18). - To scale up multisectoral malaria programmes at country and subnational levels as well as an action-oriented implementation, a research, monitoring and evaluation component should be included. The articulation of an endorsed and validated results framework with key expected results and indicators for monitoring a country programme?s multisectoral engagement activities should be considered. This results framework should also include strong political will and commitment to malaria at the highest level and inclusion of malaria elimination as an issue in national development plans (18). Countries should also explore how financing opportunities in non-health sectors can be leveraged for malaria, for example the potential of using revenues from extractive industries investments. Service provision To be effective, intersectoral action needs to be supported by high-level political leaders; ministries of health alone are not usually powerful enough to motivate other ministries or the corporate sector for effective collaboration. Adoption of malaria elimination as a national goal offers an opportunity for enactment of policies mandating intersectoral collaboration by the cabinet or prime minister's offices. Such commitment at the highest level should then be reflected at lower administrative levels, to ensure that health staff are: informed in advance about population movements and other potential risk factors; involved in planning of development projects; and has sufficient collaboration with the other sectors, whether public or private, to implement the necessary mitigation measures. Recruiting agencies and employers of migrant labour (e.g. for large-scale development, plantations and infrastructure projects) may be known or can be identified. There may be opportunities for providing migrants with information and commodities through those involved in their transport or accommodation, or through NGOs providing social services. There are good examples of collaboration with plantations owners and petroleum or gas companies in GMS. Ministries of health may lack administrative procedures for binding agreements with private enterprises; sometimes such agreements can be facilitated by involving entities with specific expertise. Efforts are required to ensure that military, police and security forces have access to malaria services. This cannot be taken for granted, because their health services may be underfunded. WHO has developed guidelines for the United Nations regarding security forces from the GMS who serve as peacekeepers or participate in exercises or training in other countries. Prophylaxis for travellers to endemic areas also needs to be supported by intersectoral collaboration with travel agencies. Producers and importers of malaria control commodities Producers of various tools for control of malaria could be engaged in malaria elimination beyond the sale of products. For example, producers can be contracted to deliver products closer to the point of use, taking advantage of commercial supply chains. This could be useful for obtaining different types of LLINs to suit different consumer demands. Producers could also be engaged in provider and consumer education, and cooperate in bundling commodities in kits with instructions for use (e.g. nets with insecticide packs for treatment). Such collaboration will also help a country to prepare for malaria-free status, for example, where some populations in receptive areas are still at risk of reintroduction, but the risk is not high enough to justify continued vector-control coverage by the public health system. The availability of consumer-friendly quality products through commercial channels could be an efficient way to reduce transmission risk. Community involvement Another crucial element is the involvement of communities, and their partnership with the health sector to empower them in their own health development. Malaria prevention must go hand in hand with community participation. Unless individuals in communities see the merits of preventing the illness, even the best-designed prevention strategies might not be used. It is necessary to understand existing behaviours that may either complement or hinder preventive measures. Knowledge, attitudes and practices should be assessed to ensure that strategies and approaches are compatible with the practices, customs and beliefs of various social groups and minorities, and to develop effective information, education and communication (IEC) strategies and targeted materials. Community and family care, and preventive practices, should be strengthened through the provision of IEC materials as well as capacity-building through mass media and community support. Health education and community participation can greatly facilitate the work, reduce the cost and help to ensure success. The supportive involvement of local people can be fostered through community awareness sessions to explain malaria interventions and their benefits. Advocacy to support collective action Advocacy can leverage political commitment, create new funding opportunities and support partnerships. Economic modelling is required to develop robust cost?benefit modelling that focuses on elimination targets. This is a core need for ongoing elimination advocacy. There are a number of global and regional malaria partnerships that could provide a platform for elimination advocacy. Advocates for malaria elimination can work within developmental frameworks, building synergies with other health and social programmes, to maximize outcomes from investment and prevent competition for increasingly scarce resources. Key elements of advocacy for malaria elimination in the GMS are likely to include (21): - this regional strategy document, supported by international health bodies, including the World Health Assembly and WHO; - a regional elimination plan with national and regional components, together with thorough costings and tools to support the business case; - core elimination advocacy messages; - provision of advocacy tools for partners; - extensive and effective community engagement; and - strong partnerships. Malaria elimination is a dynamic process. Elimination advocacy will need to adapt to new technologies and research findings, emerging successes and challenges, changes in the sociopolitical landscape of eliminating countries and changes in global health financing. The global malaria community needs to work together to ensure that the early steps are taken to reach the end goal of malaria elimination. GMS regional functions Although national leadership is the centrepiece of this strategy, there is a clear need for a supportive and coordinating platform at the regional level. The key areas of focus at regional level are outlined below. Coordination Governance and coordination of malaria activities across the GMS is essential and must be improved at both the regional and country level (see Section 4). Technical support and capacity-building To address future needs and achieve elimination of malaria, a creative and innovative approach to capacity development should be promoted at regional, national and subnational levels. National programmes should be supported and coordinated to: - develop and regularly update human resource development plans; - maintain a core technical group of adequately trained professionals with the necessary epidemiological expertise to address the new elimination challenges; - update knowledge and enhance the skills of specialized and general health staff; - ensure that training programmes are updated as necessary to support national elimination strategies (training should be oriented to tasks and problem solving and supported by regular supervision and needs-based refresher courses); and - ensure that training increases the motivation of health staff to maintain their skills and competence and remain in service. Generally, the malaria programmes in the GMS have benefited from more technical collaboration than others because of the complexity of malaria problems and the fact that drug resistance is seen as a global threat. In consequence, most of the capabilities required for control and elimination are present within each country. Nevertheless, with the adoption of a GMS malaria elimination strategy there will be additional need for training and technical collaboration in direct relevance to: - malaria elimination approaches, using WHO?s manuals and training materials, adapted to the epidemiology of GMS; - information technology, including management of geographical information; - QA for microscopy and RDTs; - new methods, such as diagnostic techniques, if and when these have been sufficiently validated for operational use; - entomological surveillance and vector-control QA. Some capabilities are probably better developed by workshops, where participants learn from each other. These should include: - advocacy and intersectoral collaboration; - management of malaria in mobile and migrant populations; and - intersectoral collaboration and management of human resources for elimination. Cross-border and regional collaboration The GMS countries belonging to the WHO South-East Asia and Western Pacific Regions share many commonalities in relation to eco-epidemiological and socioeconomic settings. Therefore, closer coordination and cooperation should be promoted through the regular exchange of malaria-related information of mutual interest. This should include provision of regular updates on the malaria situation in border areas, organization of border meetings and participation in interregional trainings. Many meetings have been conducted with representatives from GMS countries' disease control programmes to discuss intercountry collaboration, including cross-border operations. Presently, the Regional Artemisinin Resistance Initiative (RAI), which is supported by the Global Fund, supports cross-border operations. This is a difficult area because of issues of national sovereignty, and because those working at border areas may be far from the national capitals where decisions are made. As progress towards malaria elimination in the GMS gathers momentum, it may be necessary to create intercountry oversight bodies on cross-border collaboration that can meet regularly and quickly resolve any issues that might jeopardize the elimination effort. Such collaboration should be facilitated at high levels of governance, in line with the East Asia Summit decisions. In the context of malaria elimination, special attention should be given to situations where there is a risk of malaria spreading between countries. In particular, there should be a focus on endorsement of joint statements on cross-border collaboration and development, or implementation of joint border action plans, to facilitate malaria elimination measures in border areas. Product quality is also a cross-border issue, and a need may now exist for a well-coordinated and funded regional programme that involves all relevant government agencies and other stakeholders, including relevant regional bodies. Progress monitoring A coordinated six country elimination effort requires careful monitoring of progress and periodic evaluation. Priority research Regional oversight of research activities at national level is needed to minimize unnecessary duplication and to take full advantage of any opportunities for collaborative research and synergy. Information sharing

Sharing information quickly and effectively, particularly between neighbouring countries, will help to ensure a coordinated regional approach to any of the numerous potential malaria-related issues that have cross-border implications.

|